Using Web Crawling to Map US State Governments

What do governments do? These days, you can answer this question in many ways: the desire for accountability has pushed many governments to publish more and more data online. These efforts are fantastic, but they seem to have a blind spot. The data is flat. By that, I mean that they usually contain tables, budgets, pieces of information that cannot be really connected to each other. As a network scientist, I think inter-actions contain as much information as actions. Where is the dataset that tells me how public agencies interact with each other? Now the answer is simple: we built it!

The question is: how do we map interactions between agencies if they do not publish data about what they do with whom? And, once we’ve done that, how do we know we’re representing the interactions correctly? This is the result of an effort started by Stephen Kosack, which then gathered to accompany me a fantastic team with a diverse set of skills: Evann Smith, Kim Albrecht, Albert-Laszlo Barabasi, and Ricardo Hausmann. It resulted in the paper “Functional structures of US state governments,” recently published (Open Access!) in PNAS.

We realized that there is a place where agencies say what they are doing: their website. And because websites are built around the idea of interconnecting documents, they are a natural place to scout for links. Our fundamental assumption is that, when a school’s website links to its school district, they’re implicitly or explicitly saying: “What that agency says is relevant for what I do, so you should check them out.” In other words, we can and should link them in a network of agencies.

Crawling the web is notoriously complicated. Besides the technical challenges, there’s also the fact that it’s difficult to build a complete index of government websites. We did our best to follow the agency directories published by central state governments, and integrated that with data from Wikipedia and other websites specializing in listing public schools, libraries, city, and county governments.

Obviously, the picture is incomplete and it changes constantly: we did the crawl in 2014 and the web presence of governments ought to look a bit different today. However, we managed to estimate websites’ ages using the Wayback Machine (consider donating!) and we see signs of saturation: the growth of government presence online is significantly slowing down. A hint that the big picture we’re seeing shouldn’t have changed that much. So what’s this big picture? Allow me to introduce you to what we affectionately call “The Cathedral”:

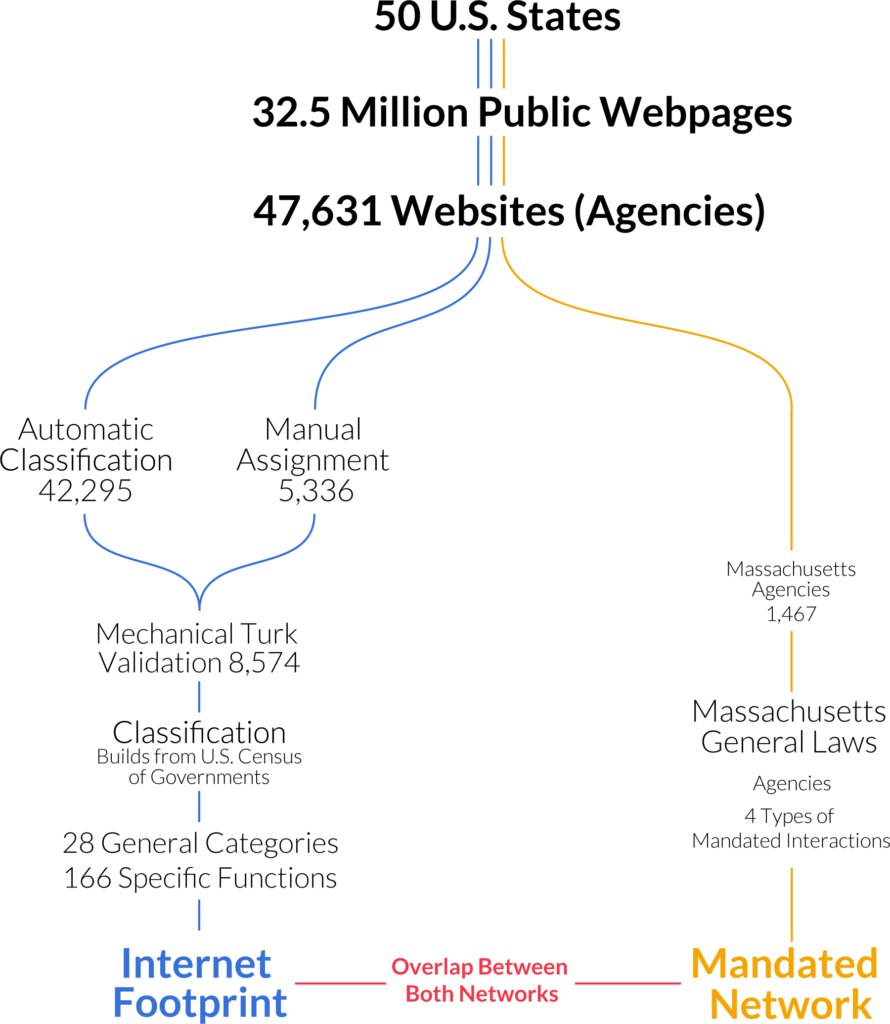

We collapsed each government agency in a two-level classification of activities into government functions. The top level is a generic activity area and the second level is a specialization inside the area. For instance, a top-level function is education. Then “primary/secondary education” and “public libraries” are two possible second level functions inside education. We built this classification by looking at the textual content of each website. Mechanical Turkers validated it. In the cathedral, each node is a function. We connected nodes if agencies, classified under one function, linked themselves to agencies classified under the other. The position of the node is determined by its centrality both horizontally — most central in the middle — and vertically — from top, most central, to bottom. The cathedral confirms our intuition of hierarchicalness: central state and local governments oversee everything and connect to everything.

We could test how much our picture overlaps with actual agency interactions, because the government of Massachusetts mandates some collaborations in its constitution. So we forced Evann to dedicate one year of her life going through the constitution of Massachusetts and noting down when two agencies were mentioned in the same article as in need of interacting. Then it took me a whole five minutes to swoop in to take the credit by testing how much the web network fared compared to the constitutional network (thanks Evann!).

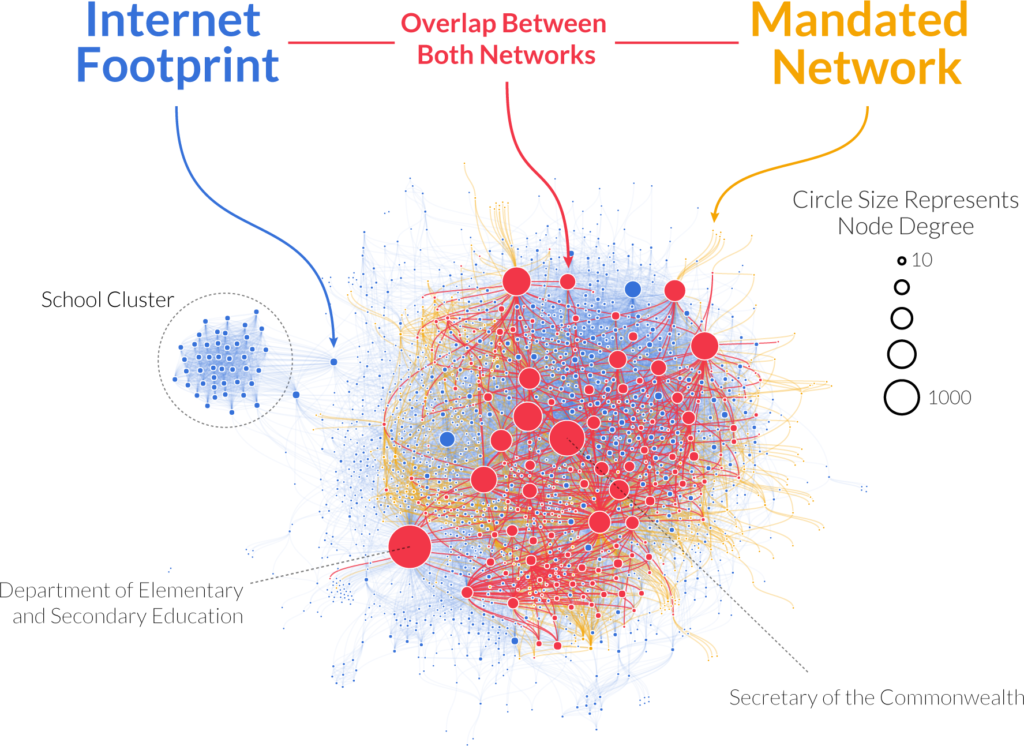

Red is web-constitution overlap, yellow is what the constitution sees and we don’t, blue is what we see and the constitution doesn’t. Click to enlarge.

The answer is “a lot, with a twist.” Agencies that are mandated to collaborate connect to each other on the web much more strongly than we expected — almost eight times as much. The majority of mandated connections are represented in the web. But the overall measure of alignment returned rather low values. How come? Because the internet reveals many more agencies than are mentioned in the constitution. And it reveals many more links too. Although some of that ought to be noise, there are ways to filter it out to end up with a network that is actually more complete than the one you’d get by looking only at the constitution.

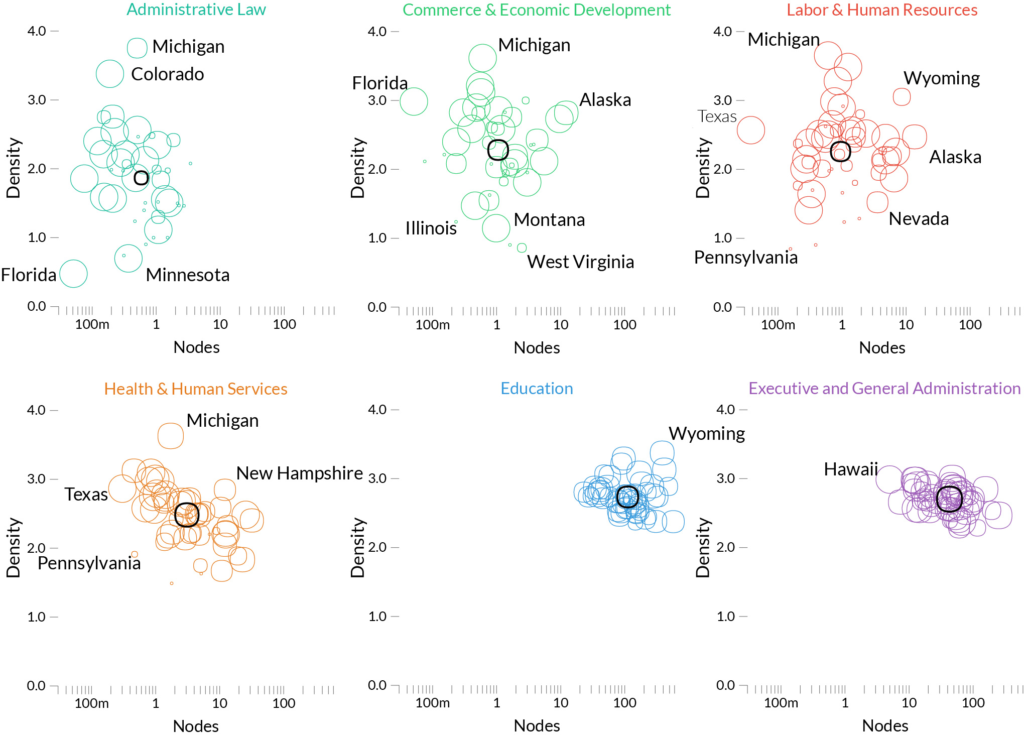

One question we wanted to answer with our data was: how can we explain differences in how states decide to implement their functions? We had a few hypotheses. Maybe it’s ideology: red and blue have… different ideas on how to do things — to put it mildly. Or maybe it’s how rich the states are: more $$$ = more complexity. Maybe it’s just their geographical position. It could be a bit of all of that, but there is one thing dominating everything else: economic structure. It’s not the amount of dollars you earn, but how you do it. Hi-tech states look like hi-tech states, agricultural states look like agricultural states, whether they are red, blue, purple, ocher, indigo, rich, or poor.

Each circle here is a state, and we look at three dimensions on how they implement each function: how many agencies they created to serve it, how big they are, how much they talk to each other. Some functions, like education, are consistently implemented the same across states — we can tell because the states’ circles are very clustered –. Others are all over the place, like administrative law. Click to enlarge.

Everything I said can be visualized in all its glory in the official website of the project: http://govmaps.cid.hks.harvard.edu/ (by Kim Albrecht). You have a few interactive visualizations, the paper, and the data. We strongly believe in open data and reproducibility: our data release includes not only the US state government networks, but also a collection of scripts to reproduce the main results of the paper.

I hope this could be a significant step forward in how we understand government actions and effects on society. Nowadays, it feels that there is a gargantuan ideological divide between sides: handing over your state to “the other side” feels like a tragedy. Our results seem to suggest that, actually, it doesn’t make that much of a difference.