Netsci 2016 Report

Another NetSci edition went by, as interconnected as ever. This year we got to enjoy Northeast Asia, a new scenario for us network scientists, and an appropriate one: many new faces popped up both among speakers and attendees. Seoul was definitely what NetSci needed at this time. I want to spend just a few words about what impressed me the most during this trip — well, second most after what Koreans did with their pizzas: that is unbeatable. Let’s go chronologically, starting with the satellites.

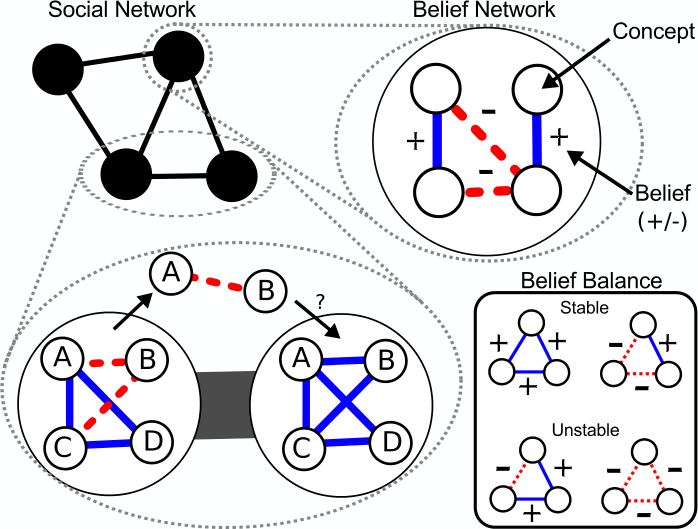

You all know I was co-organizing the one on Networks of networks (you didn’t? Then scroll down a bit and get informed!). I am pleased with how things went: the talks we gathered this year were most excellent. Space constraints don’t allow me to give everyone the attention they deserve, but I want to mention two. First is Yong-Yeol Ahn, who was the star of this year. He gave four talks at the conference — provided I haven’t miscounted — and his plenary one on the analysis of the Linkedin graph was just breathtaking. At Netonets, he talked about the internal belief network each one of us carries in her own brain, and its relationship with how macro societal behaviors arise in social networks. An original take on networks of networks, and one that spurred the idea: how much are the inner workings of one’s belief network affected by the metabolic and the bio-connectome networks of one own body? Should we study networks of networks of networks? Second, Nitesh Chawla showed us how high order networks unveil real relationships among nodes. The same node can behave like it is many different ones, depending on which of its connections we are considering.

Besides the most awesome networks of networks satellite, other ones caught my attention. Again, space is my tyrant here, so I get to award just one slot, and I would like to give it to Hyejin Youn. Her satellite was on the evolution of technological networks. She does amazing things tracking how the patent network evolved from the depths of 1800 until now. The idea is to find viable innovation paths, and to predict which fields will have the largest impact in the future.

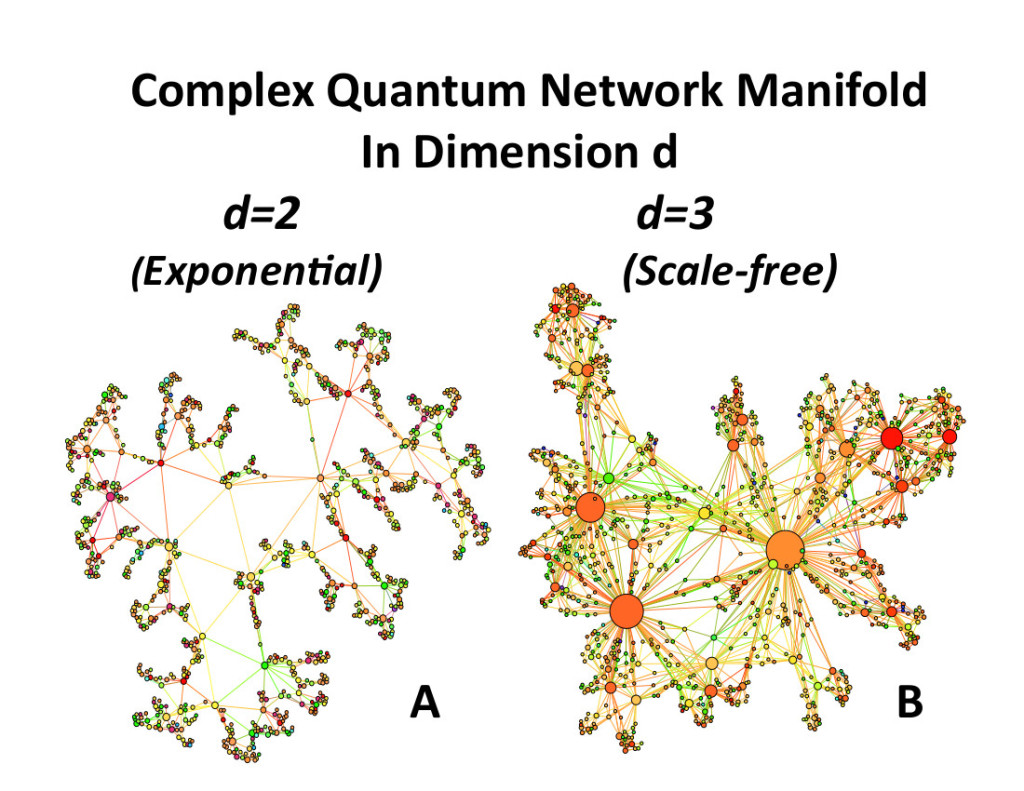

When it comes to the plenary sessions, I think Yang-Yu Liu stole the spotlight with a flashy presentation about the microcosmos everybody carries in their guts. The analysis of the human microbiome is a very hot topic right now, and it pleases me to know that there is somebody working on a network perspective of it. Besides scientific merits, whoever extensively quotes Minute Earth videos — bonus points for it being the one about poop transplants — has my eternal admiration. I also want to highlight Ginestra Bianconi‘s talk. She has an extraordinary talent in bringing to network science the most cutting edge aspects of physics. Her line of research combining quantum gravity and network geometry is a dream come true for a physics nerd like myself. I always wished to see advanced physics concepts translated into network terms, but I never had the capacity to do so: now I just have to sit back and wait for Ginestra’s next paper.

What about contributed talks? The race for the second best is very tight. The very best was clearly mine on the link between mobility and communication patterns, about which I showed a scaling relationship connecting them (paper – post). I will be magnanimous and spare you all the praises I could sing of it. Enough joking around, let’s move on. Juyong Park gave two fantastic talks on networks and music. This was a nice breath of fresh air for digital humanities: this NetSci edition was orphan of the great satellite chaired by Max Schich. Juyong showed how to navigate through collaboration networks on classical music CDs, and through judge biases in music competitions. By the way, Max dominated — as expected — the lighting talk session, showing some new products coming from his digital humanities landmark published last year in Science. Tomomi Kito was also great: she borrowed the tools of economic complexity and shifted her focus from the macro analysis of countries to the micro analysis of networks of multinational corporations. A final mention goes to Roberta Sinatra. Her talk was about her struggle into making PhD committees recognize that what she is doing is actually physics. It resonates with my personal experience, trying to convince hiring committees that what I’m doing is actually computer science. Maybe we should all give up the struggle and just create a network science department.

And so we get to the last treat of the conference: the Erdos-Renyi prize, awarded to the most excellent network researcher under the age of 40. This year it went to Aaron Clauset, and this pleases me for several reasons. First, because Aaron is awesome, and he deserves it. Second, because he is the first computer scientist who is awarded the prize, and this just gives me hope that our work too is getting recognized by the network gurus. His talk was fantastic on two accounts.

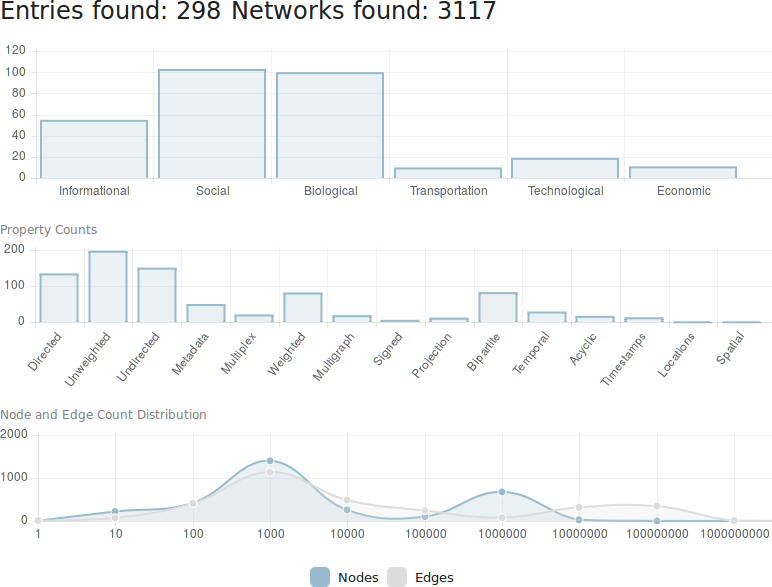

For starters, he presented his brand new Index of Complex Networks. The interface is pretty clunky, especially on my Ubuntu Firefox, but that does not hinder the usefulness of such an instrument. With his collaborators, Aaron collected the most important papers in the network literature, trying to find a link to a publicly available network. If they were successful, that link went in the index, along with some metadata about the network. This is going to be a prime resource for network scientists, both for starting new projects and for the sorely needed task of replicating previous results.

Replication is the core of the second reason I loved Aaron’s talk. Once he collected all these networks, for fun he took a jab at some of the dogmas of networks science. The main one everybody knows is: “Power-laws are everywhere”. You can see where this is going: the impertinent Colorado University boy showed that yes, power-laws are very common… among the 5-10% of networks in which it is possible to find them. Not so much “everywhere” any more, huh? This was especially irreverent given that not so long before Stefan Thurner gave a very nice plenary talk featuring a carousel of power laws. I’m not picking sides on the debate — I feel hardly qualified in doing so. I just think that questioning dearly held results is always a good thing, to avoid fooling ourselves into believing we’ve reached an objective truth.

Among the non-scientific merits of the conference, I talked with Vinko Zlatic about the Croatian government on the brink of collapse, spread the search for a new network scientist by the Center for International Development, and discovered that Korean pizzas are topped with almonds (you didn’t really think I was going to let slip that pizza reference at the beginning of the post, did you?). And now I made myself sad: I wish there was another NetSci right away, to shove my brain down into another blender of awesomeness. Oh well, there are going to be plenty of occasions to do so. See you maybe in Dubrovnik, Tel-Aviv or Indianapolis?