My Winter in Cultural Data Analytics

Cultural analytics means using data analysis techniques to understand culture — now or in the past. The aim is to include as many sources as possible: not just text, but also pictures, music, sculptures, performance arts, and everything that makes a culture. This winter I was fairly involved with the cultural analytics group CUDAN in Tallinn, and I wanted to share my experiences.

CUDAN organized the 2023 Cultural Data Analytics Conference, which took place in December 13th to 16th. The event was a fantastic showcase of the diversity and the thriving community that is doing work in the field. Differently than other posts I made about my conference experiences, you don’t have to take my word for its awesomeness, because all the talks were recorded and are available on YouTube. You can find them at the conference page I linked above.

My highlights of the conference were:

- Alberto Acerbi & Joe Stubbersfield’s telephone game with an LLM. Humans have well-known biases when internalizing stories. In a telephone game, you ask humans to sum up stories, and they will preferably remember some things but not others — for instance, they’re more likely to remember parts of the story that conform to their gender biases. Does ChatGPT do the same? It turns out that it does! (Check out the paper)

- Olena Mykhailenko’s report on evolving values and political orientations of rural Canadians. Besides being an awesome example of how qualitative analysis can and does fit in cultural analytics, it was also an occasion to be exposed to a worldview that is extremely distant from the one most of the people in the audience are used to. It was a universe-expanding experience at multiple levels!

- Vejune Zemaityte et al.’s work on the Soviet newsreel production industry. I hardly need to add anything to that (how cool is it to work on Soviet newsreels? Maybe it’s my cinephile soul speaking), but the data itself is fascinating: extremely rich and spanning practically a century, with discernible eras and temporal patterns.

- Mauro Martino’s AI art exhibit. Mauro is an old friend of mine, and he’s always doing super cool stuff. In this case, he created a movie with Stable Diffusion, recreating the feel of living in Milan without actually using any image from Milan. The movie is being shown in various airports around the world.

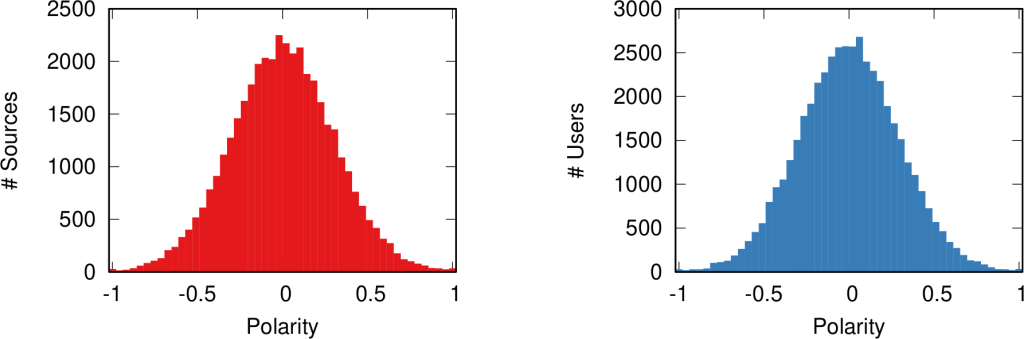

- Chico Camargo & Isabel Sebire made a fantastic analysis of narrative tropes analyzing the network of concepts extracted from TV Tropes (warning: don’t click the link if you want to get anything done today).

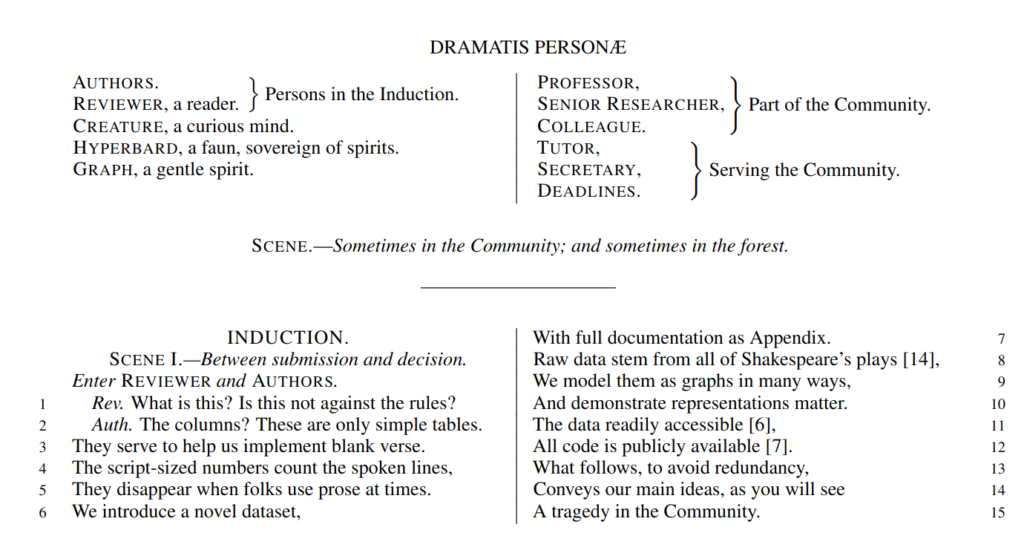

But my absolute favorite can only be: Corinna Coupette et al.’s “All the world’s a (hyper)graph: A data drama”. The presentation is about a relational database on Shakespeare plays, connecting characters according to their co-appearances. The paper describing the database is… well. It is written in the form of a Shakespearean play, with the authors struggling with the reviewers. This is utterly brilliant, bravo! See it for yourself as I cannot make it justice here.

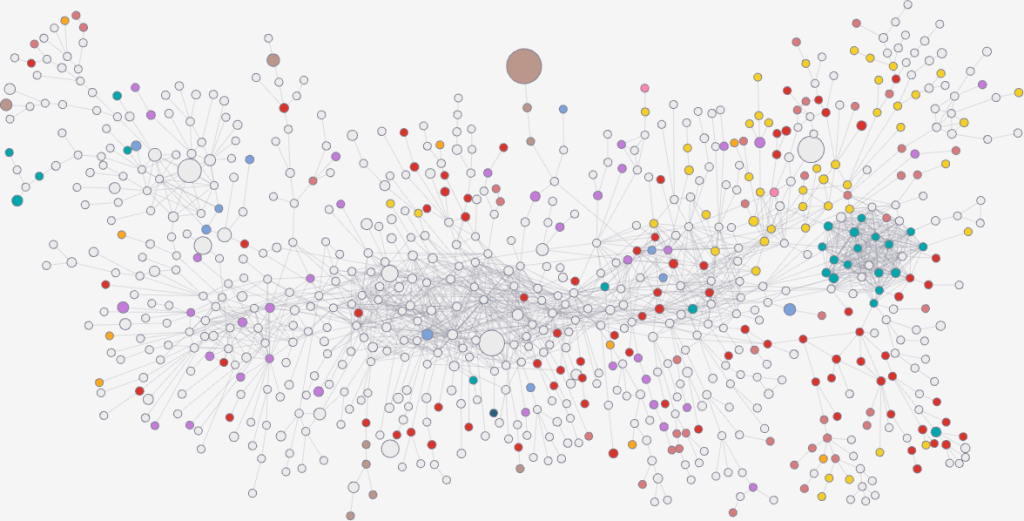

As for myself, I was presenting a work with Camilla Mazzucato on our network analysis of the Turkish Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük. We’re trying to figure out if the material culture we find in buildings — all the various jewels, tools, and other artifacts — tell us anything about the social and biological relationships between the people who lived in those buildings. We can do that because the people at Çatalhöyük used to bury their dead in the foundations of a new building (humans are weird). You can see the presentation here:

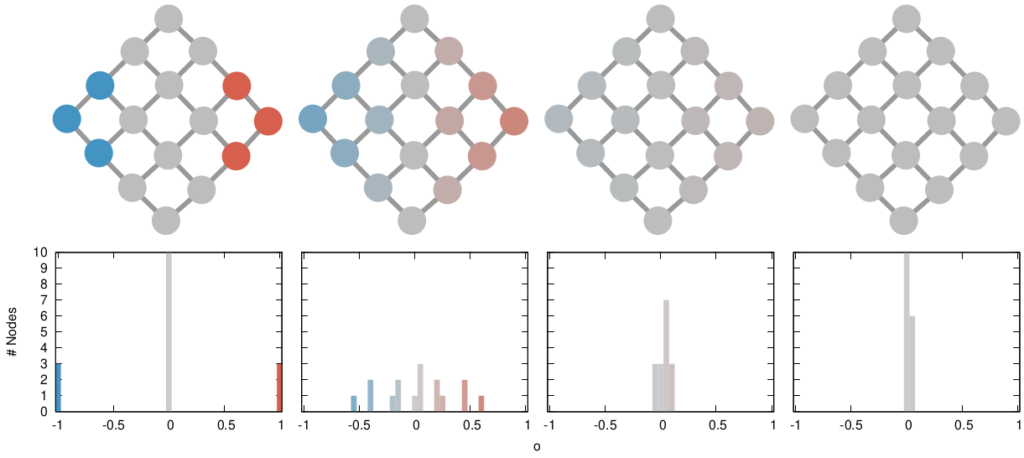

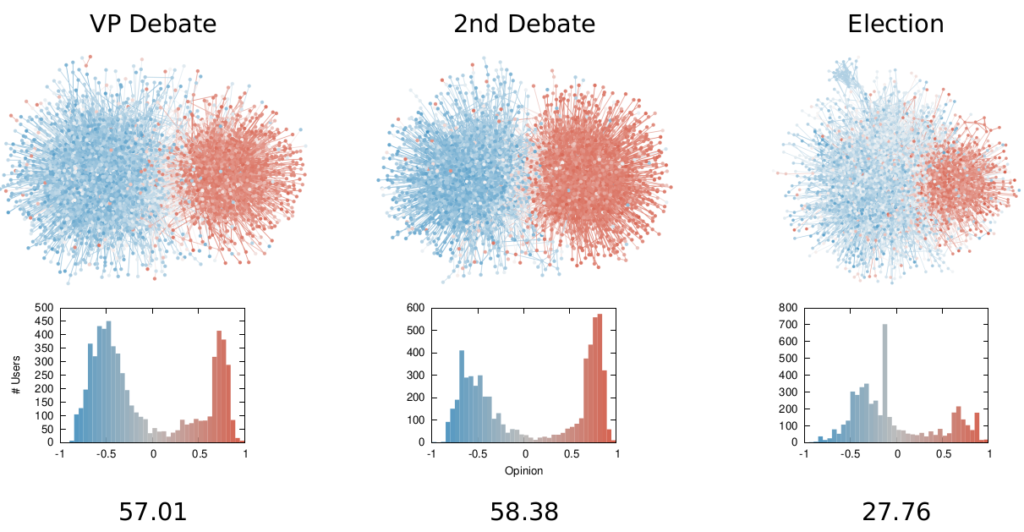

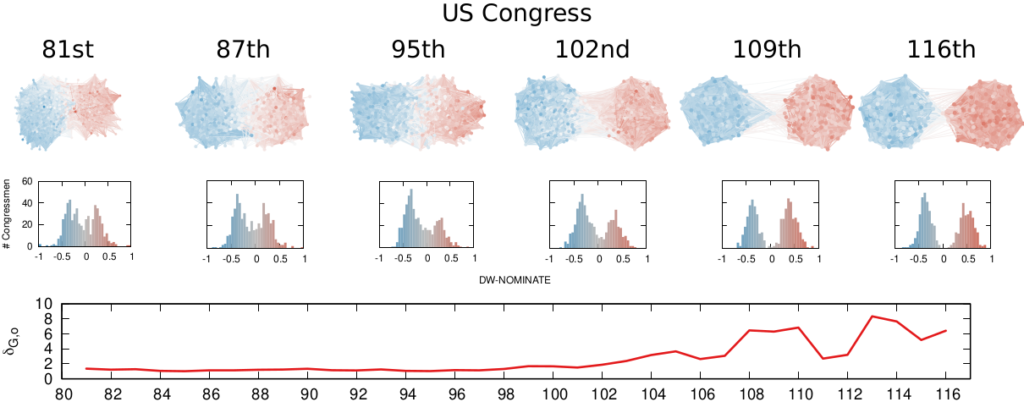

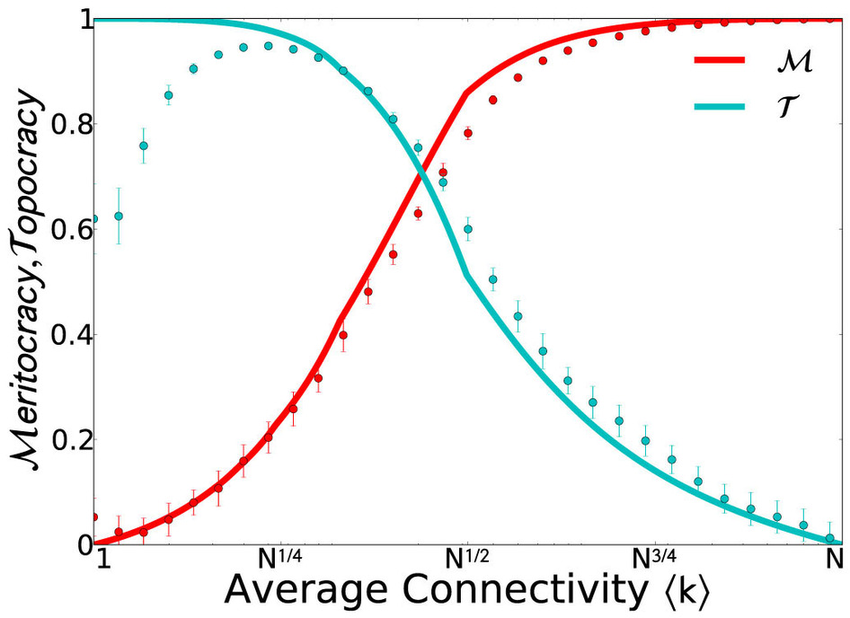

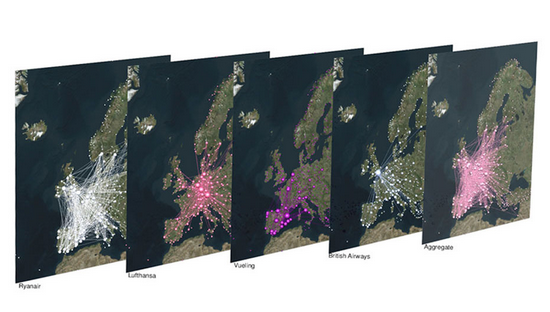

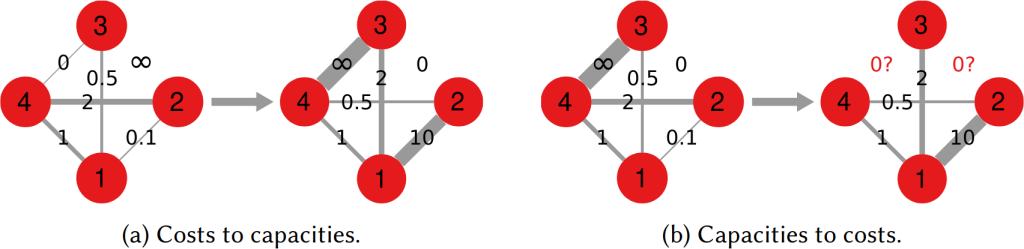

After the conference, I was kindly invited to hold a seminar at CUDAN. This was a much longer dive into the kind of things that interest me. Specifically, I focused on how to use my node attribute analysis techniques (node vector distances, Pearson correlations on networks, and more to come) to serve cultural data analytics. You can see the full two hour discussion here:

And that’s about it! Cultural analytics is fun and I look forward to be even more involved in it!

I am an associate prof at IT University of Copenhagen. I mainly work on algorithms for the analysis of complex networks, and on applying the extracted knowledge to a variety of problems.

My background is in Digital Humanities, i.e. the connection between the unstructured knowledge and the coldness of computer science.

I have a PhD in Computer Science, obtained in June 2012 at the University of Pisa. In the past, I visited Barabasi's CCNR at Northeastern University, and worked for 6 years at CID, Harvard University.

I am an associate prof at IT University of Copenhagen. I mainly work on algorithms for the analysis of complex networks, and on applying the extracted knowledge to a variety of problems.

My background is in Digital Humanities, i.e. the connection between the unstructured knowledge and the coldness of computer science.

I have a PhD in Computer Science, obtained in June 2012 at the University of Pisa. In the past, I visited Barabasi's CCNR at Northeastern University, and worked for 6 years at CID, Harvard University.